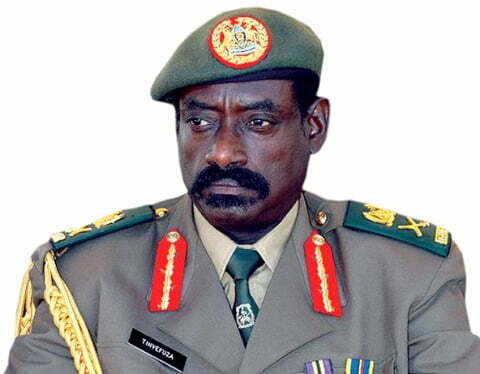

Kampala, Uganda | By Timothy Kalyegira | The Ugandan political and military landscape was shaken up in March by an army general called David Tinyefuza.

By now Ugandans keen on news about their country already know the basics of what took place. It is what preceded them, though, and what they mean that is still not clear. This story attempts to piece together the narrative.

Tinyefuza is, officially still, the Coordinator of the country’s intelligence services and a presidential advisor on military matters. He was at some stage the head of intelligence in the National Resistance Army (NRA) during its guerrilla war in the 1980s.

After questioning the way the NRA’s overall commander Yoweri Museveni was conducting some aspects of the war, Tinyefuza was arrested and spent several months in an NRA prison in the jungles of central Uganda.

After the NRA took over Kampala in 1986, Tinyefuza became a Brigade commander and later, starting in 1990 and now a Major-General and Minister of State for Defence, was deployed in Gulu to command the counterinsurgency operations against the guerrillas of the Lord’s Resistance Army.

He earned a reputation for ruthlessness while in Gulu, including ordering the frog-marching of northern politicians like Daniel Omara Atubo. But an intelligence source also says he also insisted that the soldiers’ welfare was attended to, from paying them promptly to urgent treating their wounds during and after battle.

In 1996, Tinyefuza who was also an army Member of Parliament expressed dissatisfaction at the way the army was run, declared that he wanted to quit and so began a much-reported public debate and court hearing between him and the state, which he lost in 1997, with heavy financial costs imposed on him.

He then faded off into relative oblivion, termed “katebe” in Uganda to refer to a humiliating semi-redundant status in which an army officer has not been discharged from the army but does not quite have a definite job, so he spends his days reading newspapers and collecting his salary and fuel allowance.

But the fact that over a 30-year period Tinyefuza has served in various capacities of intelligence says something about him. He still remained an asset to the government.

There is a commonly told story that reduced to desperate poverty and unable to pay his bills, Tinyefuza approached Museveni’s brother Gen. Salim Saleh and pleaded to be “rehabilitated”, after which Saleh took him to meet Museveni.

Brought before Museveni, Tinyefuza fell to the ground, pleading with the president to pardon him, which Museveni agreed to do.

Sources, familiar with what happened that day, scoff at this urban legend. They say what really happened was that Saleh made contact with Tinyefuza, who agreed to meet Museveni.

In the meeting, Tinyefuza stated his terms for returning to the government. Museveni rejected some and agreed to others, but in what was a negotiated discussion between Museveni, Tinyefuza and Saleh, not a general on his knees before Museveni pleading for mercy.

One of them must have created the rumour of Tinyefuza on his knees before Museveni to humiliate him.

It might be Tinyefuza’s ability to work covertly, or his skill at gathering information, perhaps his personal organizational habits that has kept himas an integral part of the NRA, UPDF and army High Command despite his rebelliousness.

Exactly what makes him an asset to the government has never been explained to the Ugandan public.

But if Museveni, a trained intelligence officer himself, saw it fit to appoint Tinyefuza to head NRA intelligence operations in 1982 and in 2005 become the coordinator of national intelligence, then it has to be assumed that Tinyefuza is at least a competent intelligence officer.

Too competent, in fact, that this year he has become a threat to the Museveni government.

It all started on February 17, 2012 when David Munungu Tinyefuza abruptly changed his name from Tinyefuza to Sejusa. Tinyefuza in Runyankore and Sejusa in Luganda mean the same thing: “I don’t regret.”

However, Tinyefuza explained before a church congregation in March that his true given birth name is Sejusa and it is Tinyefuza that he adopted in order to enable him join Masaka Secondary School.

In that sense, then, by formally establishing his name as Sejusa, Tinyefuza might have been seeking to return to his roots, to a sense of his true origins.

This by itself might suggest that in recent months or years he has been in a reflective state of mind, re-thinking his career, life, choices and future options.

In February 2013, after weeks of Kampala’s news media and political circles being dominated by speculation and talk of a possible military coup in Uganda, Tinyefuza spoke out.

He sent a statement to the Daily Monitor warning that those who were stoking up the growing discussion about a coup were trying to divert Ugandans from the real issues concerning how they were governed.

In that statement (which is now significant given recent developments), Tinyefuza warned that anyone who attempted to stage a coup would be defeated by “a people popular uprising which is legitimate.”

“The central issue, however that is facing us and indeed staring us in our faces, which I think is causing all these frictions is how to manage the different forces that are taking central stage in the country,” he added.

Tinyefuza did not name the people he claimed were behind the coup talk but it would appear he was sending a message to some personalities high up in the army or in the government.

Then on March 4, 2013, a number of armed men staged an apparent attack on the lower military barracks near the army general headquarters at Mbuya in Kampala.

Within hours, the then army spokesman, Col. Felix Kulaigye, was telling a press conference that this attack had been staged by thugs and not political rebels.

Then a few days later, Gen. Tinyefuza sent another statement to the Daily Monitor. The Daily Monitor published it on its front page on March 7, 2013.

Tinyefuza’s statement was in the form of a letter requesting the Director-General of the Internal Security Organization, Lt. Ronald Balya, to investigate Tinyefuza’s allegations that a number of high-ranking army generals, including President Museveni’s brother Gen. Salim Saleh and the Inspector-General of Police, Lt. Gen. Kale Kayihura, Saleh’s sister-in-law Kellen Kayongo and others had been behind the Mbuya attack, and not armed thugs.

For Tinyefuza to mention fellow army generals by name was, in itself, an alarming development. He had been guarded about mentioning anyone trying to spread coup talk but in the letter to the ISO director-general named generals.

Tinyefuza’s naming the plotters behind the Mbuya attack can only mean that they actually were the plotters or that he has or had personal conflicts with the people he named in his letter that have reached a point of enmity and he felt he had nothing more to lose by naming them.

It was the clearest example that something had cracked within the Ugandan military, much more serious even than the divisions caused or highlighted by the four NRM “rebel” MPs.

The intention of this apparently fake attack, Tinyefuza implied in his letter, was to frame him and other senior army officers as well as senior politicians opposed to what Tinyefuza termed the “Muhoozi Project.”

There also was a plot not only to attack public premises in order to frame those opposed to the “Muhoozi Project” but also to outright assassinate some of them.

The “Muhoozi Project” is the nickname in Uganda for a plan, or perception of a plan, many years in the making, by President Museveni to prepare the groundwork in due time for his son, Brig. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the Commanding Officer of the Special Forces Command, to rise through the army ranks and once established, succeed his father as Uganda’s head of state.

The rumours of such a plan or impression that such a plan might be underway began in August 1999 when, after his wedding the month before, Kainerugaba went to Britain to enroll in the Royal Military School at Sandhurst, a cadet officer training academy.

Given recent developments, the sequence of events since last year becomes critical in helping us understand what exactly is going on.

In his letter to the Director-General of ISO, Tinyefuza gave the impression that he was a concerned bystander, his life uncertain but helpless to prevent this framing and hoping ISO would investigate it.

Now we know that was not the case.

He wrote the letter published by the Daily Monitor not as an inquiry seeking clarification of rumours, but a statement that he believed the rumours and wished the Ugandan public and those rumoured to be part of the Mbuya attack plot to know that he knew about their intentions.

And what’s more, he was not going to sit around and wait for an ISO investigation he felt sure would lead nowhere but was already making plans to beat this intrigue. He was going to Britain.

There is a missing part of this story. President Museveni has still issued no statement on the allegations by Tinyefuza. Dramatic events took place around four media houses being closed, protesting journalists hit with police tear gas, the media houses were re-opened after eleven days and Tinyefuza issued a much listened-to statement in a BBC World Service interview.

But in all this, Museveni — who these days usually has something to say about almost anything major and minor going on in Uganda — has not yet spoken out about the claims by Tinyefuza, the awkward subject of an alleged Muhoozi Project and the attack on Mbuya.

Significantly, another important person mentioned by Tinyefuza in that letter whom Tinyefuza claimed was also listed for framing or assassination, the Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi, has not said a single word about Tinyefuza’s allegations.

Kayihura blasted Tinyefuza over his remarks, as did the former Chief of Defence Forces, Gen. Aronda Nyakirima (also on that list of top-ranking officers to be liquidated), and many others spoke out.

But two men have not said a thing: Museveni and Mbabazi. Museveni’s silence is somewhat understandable since if he speaks out he must, on the record, confirm or deny that he plans or does not plan to have his son succeed him.

It is Mbabazi’s silence that is the more mysterious. What does Mbabazi know and why is he silent?

So Mbabazi’s total silence over Tinyefuza’s allegations might be more telling than Tinyefuza’s outspoken remarks in his letter to the ISO boss or on the BBC on June 18, 2013.

It is possible, too, that Museveni’s silence is because of Mbabazi’s silence, not sure what to say or when to say it until he has an idea of what Mbabazi is thinking.

In his BBC interview, Tinyefuza did not refer to the Mbuya attack or the generals he had alleged in his March 7 letter to the Daily Monitor had staged the attack.

Instead, he concentrated on Museveni, calling for the ending of Musveeni’s rule by any means necessary.

Was Tinyefuza implying that he believes the “attack” on Mbuya might have been masterminded by the one who has remained silent in all this, whom everyone is still waiting to hear from?

Putting all this together, the sequence of events since last year would indicate several notable things.

First, that Gen. Tinyefuza was reflecting on his life in 2011 and 2012, resulting in his getting back to his “authentic self” and thus his given name at birth. He would have been reflecting on his late father and reassessing his life and political calling. Perhaps he had been plotting something all along.

Secondly, if Tinyefuza’s allegations are correct, then the coup talk in Kampala was indeed preparing the country for a possible military incident somewhere, not known at the time, and Tinyefuza either knew it or suspected it coming, based on his intelligence information.

Thirdly, however, it also suggests that the state or some figures in it were suspicious of Tinyefuza who in late 2011 had decided to undertake the removal of the Museveni government by force of arms, hence his change of name, or rather his return to his true name and therefore, a renewed sense of himself.

While the state was suspicious of Tinyefuza as a potential threat, it appears it did not realize in time that he had become an actual threat, no longer a potential one, planning under the radar.

There has clearly been a breakdown of intelligence in as far as Tinyefuza is concerned or perhaps there was no breakdown and Tinyefuza has his allies in the army and the intelligence services, in the same way the former presidential candidate Kizza Besigye seemed to have which made possible his safe escape into exile in August 2001.

Where all this now leads is what Uganda must await. Older Ugandans, reading this, cannot help but be reminded of the intrigue and plotting during the last year of the Obote II government.

Museveni the veteran intelligence officer will no doubt be thinking night and day about the new threat posed by Tinyefuza (or Sejusa).

Tinyefuza stands for the regular NRA and UNDF officer Ugandans are used to, a man with no personal convictions, content to get free army fuel and allowances, engage in business, live comfortably and while he might resent it, left Museveni rule on and on as long as Tinyefuza’s children attend good schools.

But what does the new Saul-become-Paul man called Sejusa stand for? He returns to his original name and spiritual roots in the Balokole church of his parents, warns against the coup talk, sends letters to the media, takes off to London and finally openly calls for the overthrow of the Museveni government on BBC.

Tinyefuza, it should not be forgotten, left some materials and computers at his home and office and intelligence agents searched these two places and took away computers.

Something must have been found on those computers that tells the story of what Tinyefuza is planning.

It is this story of what Tinyefuza is planning that will shape Uganda for the next few years. Ugandans need only start observing how the police and the state have been behaving since Tinyefuza’s office was searched.

It might explain why the police now trails Besigye everywhere he goes even more than ever, why no chances are being taken with populists like Kampala Mayor Elias Lukwago and Kisekka Market which is Uganda’s de facto Tahirir Square, why the police orders all taxis in Kampala to remove their tinting plastic film from the windows and windscreens and why KFM, Red Pepper, Dembe FM and Daily Monitor were briefly shut down.

It is the story of what lies ahead for Uganda between 2013 and 2016.