Kampala, Uganda | By Asuman Bisiika | With a history of political violence, heroism and patriotism is a touchy issue in Uganda. There is likelihood that heroes coming from people who fought in the various wars that plagued Uganda’s political history.

Which is why it calls for a dispassionate approach. Yet it is difficult for me to claim any dispassionate standing. When I was still an active political cadre (don’t mind which country or revolution in which I participated), I used to face the challenge of explaining the significance of the assumption of state power vis-à-vis the thinking and physical actions that precede it.

It was difficult to explain to the people that the thinking (ideology) and physical actions (the armed struggle) that precede taking over state power was as important as the event of taking power. And that the sustainability of the revolution was also as critical as the assumption of power.

Without the thinking to inform the physical actions, the struggle would be limited to merely taking over state power; the quick-fix kind of attitude commonplace with military coup plotters. Without the ideological anchor, the sustainability of the revolution strains leading to what students of revolutions call ‘revolutionary regression’.

The sustainability is not the rhetoric oratory of cadres sugared with wordy bombast and quick-tongued delivery or diction. Revolutionary sustainability is about tangible and intangible achievements that constitute a legacy.

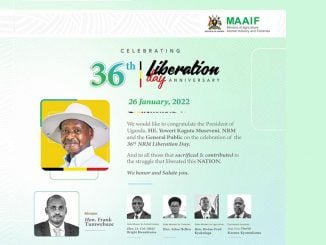

Which begs the question: As the National Resistance Movement (NRM) revolution celebrated 34 years in power in January 26, 2020 what are the achievements with an enduring legacy? To put it another way, apart from the assumption of state power on January 26, 1986 and the winning of several elections, what moral mandate does the NRM have to rule?

This essay is not intended to praise or critique the NRM government; but rather, I take it as a personal observation and assessment.

The most significant aspect of the NRM struggle has been the demolition of the colonial state superstructure and the thinking that made it. The central plunk of the colonial state was the Chief. He could be addressed variously as King, Paramount Chief or merely Chief.

He could be native traditional leader or appointed by the state like the case of Semei Kakungulu or appointed by the paramount chief or king. But his brief remained the same: namely to run the affairs of the state on behalf of the colonial administration which was far removed from the people.

The Chief levied and collected taxes, arrested you for defaulting on tax payment and released you as he willed. The chief’s responsibility was to the colonial administration not the people he ruled or administered. And as long as he did not ‘annoy’ his colonial administration masters, he could do with the population as he wished.

The immediate post-colonial administrations, either for lack of ideological clarity or confidence, just inherited the entire colonial state apparatus. With the benefit of retrospection, we can now say that the good old colonial system was so much entrenched that it needed more than just being an independent state to dismantle.

That is why January 26 1986 is significant for the NRM revolution because the NRM would not have dismantled the colonial state without the assumption of state power.

The Chief (be it the Sub County Chief or the District Chief Administrative Officer) is now supervised by an elected leader. Cases where the district council (as a representation of the people) has dismissed the CAO or Town Clerk are many. Although there may be some weakness here and there, this re-organisation of the state superstructure is irreversible.

Lengthy regime

The leadership of the NRM revolution have actually ‘overstayed’ in power given Uganda’s standards of regime length. In spite of the accusations that lengthy regimes breed dictatorial tendencies, NRM revolution’s lengthy stay (over stay?) has had its advantages.

It has bred consistency in policy rationalisation, harmony and systematic approach to what used to be referred to as intractable national challenges like the lost counties, restoration kingdoms etc.

For Ugandans of my age group, even the novelty of having a president rule for more than ten years has its psychological feel-good factor. For instance, a besieged regime is most unlikely to hold elections (poorly managed or otherwise) three times.

The holding of three consecutive elections (their quality notwithstanding) may be seen as a small matter but it remains a precedent that may turn out to be irreversible. Any leader thinking of postponing elections (1971 and 1985) for whatever reasons would quickly be suspected to harbour dictatorial tendencies.

The benefits for a lengthy regime, as opposed to what had become the Uganda’s staple of short-lived governments, are many. Economic stability, relative peace in most parts of the country, improvement in the delivery of social services and the removal of non-tariff road military-manned barriers commonly called road blocks.

Diplomatic Stability

Since 1986, the government has successfully fought rebellion after rebellion. However, even when the rebels were thought to be at their highest in strength and motivation, they never caused a stalemate as to render the state ineffective as is the case in DR Congo.

As we write this, the Lords Resistance Army, the only remaining rebel group has been weakened to a level where they are incapable of sustaining any serious offensive. Plus, they are thousands of kilometres away from Uganda.

But the most significance aspect of the fight against rebels is that they were tapered by a shrewd diplomatic effort. Countries fighting rebellions tend to face the challenge of explaining the humanitarian consequences of the war to the international community.

It therefore takes serious diplomatic efforts to be understood by people far away who think rebellions (armed or otherwise) represent disagreement on policy issues. But thanks to the diplomatic efforts, even the issue of Internally Displaced People’s (IDP) camps could be explained despite several voices calling them concentration camps.

The leadership of the revolution, despite several regional geo-political challenges has retained a deserving respect regionally and internationally. This might be viewed as a small matter, but when one hears of sitting presidents being indicted in courts like the International Criminal Court and other tribunals, one realises that it takes more than being a president to be a respected regional player.

Some of the challenges facing the leadership in Zimbabwe can be traced to the failure by the Harare leadership to realise that it takes a leader to reconcile exogenous influences with endogenous interest. The leadership of the NRM revolution has balanced these very well.

Anecdote

When I was writing this piece, a friend asked me to include free Universal Primary Education, (UPE), free Universal Secondary Education (USE), roads and many other things as some of the achievements of the NRM revolution.

But as I said earlier, this essay is about the structural changes with long lasting impact on the politics of Uganda. The introduction of UPE, USE and the construction of roads are obligatory administrative actions. This paper limits itself to deliberate ideological actions.