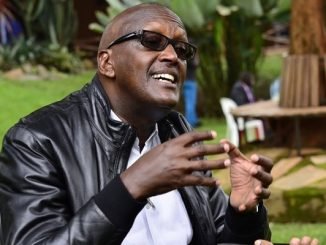

Kampala, Uganda | By Timothy Kalyegira | The former Chief of Military Intelligence and Director-General of the Internal Security Organization (ISO), Brig. Henry Tumukunde, has been dismissed from the army and given a “severe reprimand,” but otherwise sees himself now free of a nearly eight-year period in a state of virtual house arrest.

The disciplinary action against him came in connection with comments he made during an appearance on a talk show at CBS FM in Kampala, where he criticized President Yoweri Museveni’s handling of affairs in Uganda.

To many people who heard of the verdict, there was something hard to understand about it. Tumukunde has been held under house arrest at the Officers’ Mess at Kololo, has made endless trips to the Makindye Military Court and could not travel out of the country.

Surely his offence must have been serious. But after nearly eight years of waiting, the ruling sounded almost like Tumukunde’s crime was to have sat in a high command meeting and chatted with friends on Facebook rather than actually taking part in the discussions. It seemed so petty.

The perception in Uganda is that certain forms of punishment no longer need be the traditional jail term at Luzira.The worst form of punishment for the propertied class is simply to let their businesses and investments bleed to death.

This form of punishment has been termed “katebe”, where an army officer is left in a state of limbo. He can neither take part fully in army life and activities, nor can he be discharged from the army.

There is also the perception that Tumukunde was being persecuted for daring to state on radio what needed to be stated and the only difference between him and so many other officers and men was that he had the daring to do so.

Because many other court cases involving prominent opposition and ruling-party politicians have clearly been politically motivated – the best-known of them being those surrounding Col. Kizza Besigye — the Ugandan public sees in every prosecution and arrest a political motive.

However, Uganda being what it is, this case like all the others before it will soon be forgotten. It will be written about in newspaper columns, analysed on TV and radio talk shows, and be discussed in bars and in Internet forums. Within a month, the society will have moved on back to its daily routine.

Tumukunde as the army’s Fourth Division Commander during the 2001 general election campaign played an active and public role in President Museveni’s re-election campaign. He made no attempt to conceal his partisanship and the ruling NRM made no attempt to point out to him the problem of a serving army officer actively campaigning for a political candidate.

As director of military intelligence, Tumukunde clashed with colleagues such as Col. Elly Kayanja.

Tumukunde will now face an additional problem, and that is the way the Ugandan state and society are organized today. While the constitution states that power belongs to the people, the facts of every day life in the country reveal that power belongs to the president. It is he who determines what goes, who gets appointed, who wins major government contracts, who gets pardoned, who is given loans or free money by the Bank of Uganda and who is given tax holidays.

Tumukunde can only now go into business or into opposition politics. The most likely path will be business, where he will find there is little room to flourish because there is currently little real purchasing power in the economy.

Most of the major commercial property owners in Uganda depend on the state for their existence. It is either directly looted from the treasury or secured through government contracts and tenders, state protection in cases where they face the law or Uganda Revenue Authority taxes or a word from President Museveni protecting these business owners.

Since Tumukunde is now viewed as a rebel army officer, business is going to be difficult for him. Many politicians and military and security officers will fear to patronize any restaurant, say, or hotel he starts lest they are identified as being in collaboration with this rebel.

Eventually, the eight years in the wilderness that he has faced and the prospect of a difficult environment within which to operate will break him. We are very likely to hear of quiet mediation talks taking place between Tumukunde and Gen. Salim Saleh to have him “rehabilitated” and once that’s done, he’ll return to the life of privilege he had gotten used to.

Expulsion of NRM MPs

This brings us to the expulsion of four Members of Parliament from the ruling NRM party: Theodore Sekikubo, Muhammad Nsereko, Wilfred Niwagaba and Barnabas Tinkasimire. For the last two years, since the debate over Uganda’s oil contracts in 2011, these young MPs have become increasingly vocal about the state of affairs in Uganda today.

Like Tumukunde and others before them, they identified the NRM government and President Museveni to which they belong and whom they serve as being a part of the problem, if not the root of the problem itself.

Their view was that in the best interests of the nation, they had a duty to point out the corruption, mismanagement of government resources, unexplained deaths of prominent political figures and rigging of elections. As for those who wondered why they remained in the NRM when they could clearly see its defects, their reply was that one could remain in the party and try to influence internal reforms.

The NRM’s top officials argued that while there were undeniable weaknesses and faults in the party, going out to the media and at public rallies to denounce an organization that one belonged to was no way to address internal problems. It was simply a lack of discipline.

In mid April, the NRM’s disciplinary committee decided to expel the four MPs. The Prime Minister and Secretary-General of the NRM, Amama Mbabazi, further moved to have the MPs expelled from the party. They insisted they could not be expelled. Some NRM officials said it was the party that had made them and reserved the right to expel those who disagreed with it.

The MPs argued that while they had contested the 2011 general election on an NRM ticket, they also had personal appeal in their constituencies. They had won on the basis of their loyal following, including getting the votes of some constituents who were not NRM supporters and so, if anything, they as candidates had done the NRM a favour by bringing victory and personal supporters to the party, not the other way around.

This, then, was the political situation in April 2013.

Many watchers of Ugandan politics started to feel that they had seen all this before. The nature of politics in the country over the last decade is such that it has settled into a predictable routine. Museveni remains firmly in power, controlling all levers of control, unchallenged by anyone.

They watched with deep disappointment Major-General David Tinyefuza, who first pointed out the NRM’s contradictions in 1996 return to the government after declaring that he had resigned from the army. They saw the respected EriyaKategaya, after criticizing the NRM and his childhood friend Museveni in 2003 for trying to create a life presidency, return humiliated to the government.

The country heard with dismay in 2005 that MPs were paid five million shillings to vote to lift presidential term limits from the 1995 constitution. This was the most disappointing development of all.

Ugandans have read and heard about prominent opposition MPs and even opposition party leaders denounce the NRM government by day but pay secret visits to State House at night, dressed in disguise, to meet the president. Some once-vocal opposition voices, like Winnie Byanyima and Anne Mugisha, left the political scene to join the work of international relief organizations.

Against this background, the Tumukunde saga and the fate of the expelled NRM MPs are interesting political stories and will not go unnoticed. But in the end, the Ugandan public has been disappointed enough and seen enough not to expect much from these developments.

It will not come as a surprise to hear that the expelled party MPs have met President Museveni at his Rwakitura home or that Tumukunde has been appointed a special presidential adviser for something.

Uganda has become as boring and predictable as that.